Developing and Selecting Digital Clinical Measures That Matter To Patients

Digital measures offer the promise of transforming how we define health and evaluate treatment. To realize this potential, we must prioritize resources to focus on digital measures that are most meaningful to patients and most informative. Without patient-focused measurement, and with the pace of digital innovation, we risk entrenching low-value innovation and experiencing the digitization of health measurement that does nothing but introduce digital assessments that are ineffective, burdensome, and reduce quality and efficiency in clinical research and care. We recommend that all stakeholders involved in digital measure development — from vendors to clinical specialists — use the framework we proposed in Digital Biomarkers and immediately implement strategies to engage early and continuously with patients and their representative groups.

With the rise of connected sensing products such as smartphones and wearables, the possibilities of measuring individuals’ biological processes, and characteristics of how they feel and function, are seemingly infinite. Researchers and clinicians have the opportunity to go beyond brief snapshots of data captured by traditional in-clinic assessments, to redefine health and disease.

Patient engagement, early and often, is paramount to thoughtfully selecting what is most important to measure.

Regulators encourage stakeholders to have a patient focus but actionable steps for early and continuous engagement are not well defined. Without intentionally pursuing patient-focused measurement, clinicians, researchers, and digital product vendors risk entrenching digital versions of poor traditional assessments and proliferating low-value tools that are ineffective, burdensome, and reduce quality and efficiency in clinical research and care.

Let’s consider an example of how a sub-par measure has permeated the field. The 6-minute walk test (6MWT) is widely used in research and care across a broad range of conditions including cardiovascular, pulmonary, inflammatory, central nervous system (CNS) diseases, and post-op patients. While the evaluation is cheap and requires little training, the 6MWT is a poor measure, showing inconsistent correlation with clinical endpoints such as mortality, lack of specificity in some patient populations, and systematically excluding non-ambulatory members of other patient populations. Despite criticism of the measure from both patients and clinicians, the 6MWT has been widely adopted by professional societies and frequently included as an endpoint in clinical trials.

How can we ensure that new digital measures are effective in detecting a change in what matters to patients in their everyday lives?

We recommend the following four-part framework that synthesizes current best practices to describe principles for selecting and developing measurements in research and care that are meaningful for patients. We go further and propose the next steps to drive forward the science of high-quality patient engagement in support of measures that matter in the era of digital medicine.

As digital health innovation roars ahead of traditional clinical development timelines, we invite you to adopt this framework and next steps to help us build a digital future of health measurement that better serves patients, regulators, the clinical decision makers, and your bottom line.

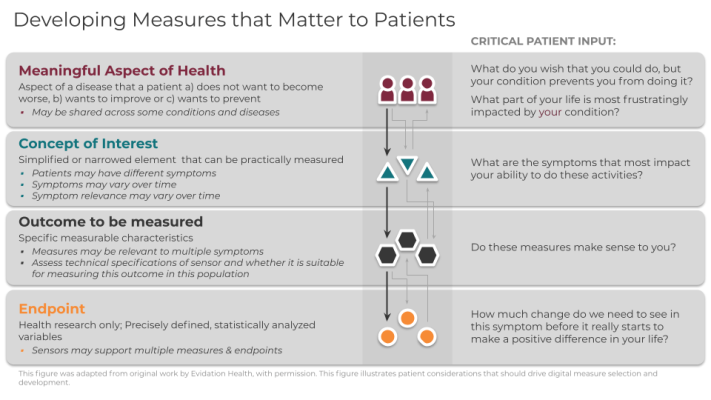

Framework for meaningful measurement: A four-step process

To evaluate the meaningfulness of signals derived from digital sensors, the following four-level framework is useful:

- Meaningful Aspect of Health (MAH)

- Concept of Interest (COI)

- Outcome to be measured

- Endpoint (exclusive to research)

In order for you to deploy this framework effectively, you must follow levels 1-4 sequentially and in partnership with patients at every step. You should define the meaningful aspect of health (MAH) before selecting concepts, outcomes, or endpoints (exclusive to research) to ensure patient-focused measurement. It is critical that you recognize that incorporating patient input is a dynamic process that requires more than a single, transactional touchpoint in a focus group, but rather is conducted continuously throughout the measurement selection process.

1. Meaningful Aspect of Health

A meaningful aspect of health (MAH) broadly defines an aspect of a disease that patients a) do not want to become worse, b) want to improve or c) want to prevent. Patients may describe specific and unique activities of their day such as fear of falling down the stairs, or a desire to maintain independence by being able to walk to the bus stop. Such activities can be grouped into an MAH category that can be readily assessed in care or research. For example, walking independently outside in the yard or the ability to make it around the grocery store can be grouped together as the ability to perform ambulatory activities. For a treatment or intervention to be proven beneficial, researchers and clinicians should strive to achieve positive changes in the specific daily activities that patients report.

2. Concept of Interest

Once you have identified the MAH, you can define a concept of interest (COI). The COI is a simplified or narrowed element of a MAH that can be practically measured. A single MAH can have multiple concepts depending on patient input. A MAH of performing hand-dependent activities could be simplified and defined as non-purposeful upper limb movement in a Parkinson’s population and joint pain intensity in a rheumatoid arthritis population. Selecting an appropriate COI is a crucial step in narrowing the MAH into a targeted aspect for measurement. Patient input is critical to ensure the selection of a COI that is most important for a particular patient group.

3. Outcome to be measured

Next, you can select the outcome to be measured. Outcomes are the specific measurable characteristics of the disease that evaluate the MAH as defined by the COI. Regardless of whether the outcomes are measured using clinical outcome assessments (COAs), or biomarkers, it is crucial that they reflect the patient-focused COI. A wearable accelerometer, for example, can capture steps per day, duration of walking bouts per day, or frequency of walking bouts per week to get an expanded view of how a disease impacts walking capacity day-to-day.

4. Endpoints

Endpoints are precisely defined variables intended to reflect outcomes of interest that are statistically analyzed to address a research question. As such, “digital endpoints” are only relevant in research and are not part of routine care. In clinical trials, endpoints measure clinical benefit related to improvement in how patients feel, function, or survive. A key difference between an outcome and an endpoint is that researchers must be able to clearly identify if endpoints were achieved, or not.

The importance of identifying the meaningfulness of a digital measure, and in turn a digital endpoint, during industry-sponsored trials of new medical products, is illustrated by FDA guidance regarding developing drugs for the acute treatment of migraine. In this regulatory guidance, sponsors are advised to develop a co-primary endpoint that best aligns the study outcome with the symptom(s) of primary importance to patients.

Why Meaningfulness Matters

Prioritizing the identification and development of digital measures that are most meaningful to patients will likely broaden acceptance and adoption of digital measurement in care and research. Currently, there are a wide array of digital measures being developed across technologies, therapeutic areas, use cases, and populations. If this trend continues, disjointed and unfocused measure development will complicate interpretation and comparison of results inhibiting the development of strong bodies of evidence supporting digital measures in the service of health.

There is no place for technological determinism in patients’ lives. This four-tier framework is already well established and should be foundational to measurement in digital medicine. This framework should be used across the full spectrum of digital measures, regardless of regulatory status.

Patient Engagement is Paramount

Patients and their care partners should be active participants engaged throughout the selection and development of every digital measure. To support this effort, we recommend that developers, clinicians, and researchers reevaluate processes for more continuous patient engagement during measure development and selection in clinical care and research. It is critical that patient engagement with respect to the development and selection of digital measures be recognized as distinct from usability testing of the measurement technologies.

Call to Action

Digital measures of health require significant resources to develop for use in clinical trials. To ensure your efforts are successful and return value to your organization and the patients we all serve, you must begin planning for the incorporation of patient input at the inception of each R&D program and clinical trial. We recommend that development teams coordinate with patient advocacy liaisons within their organizations to identify patient partners and appropriately scope for patient engagement activities in their timelines and budgets. Sponsors, vendors, and patient groups can build upon principles previously described by the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Meharry Vanderbilt Alliance, and FDA’s Voice of the Patient Reports.