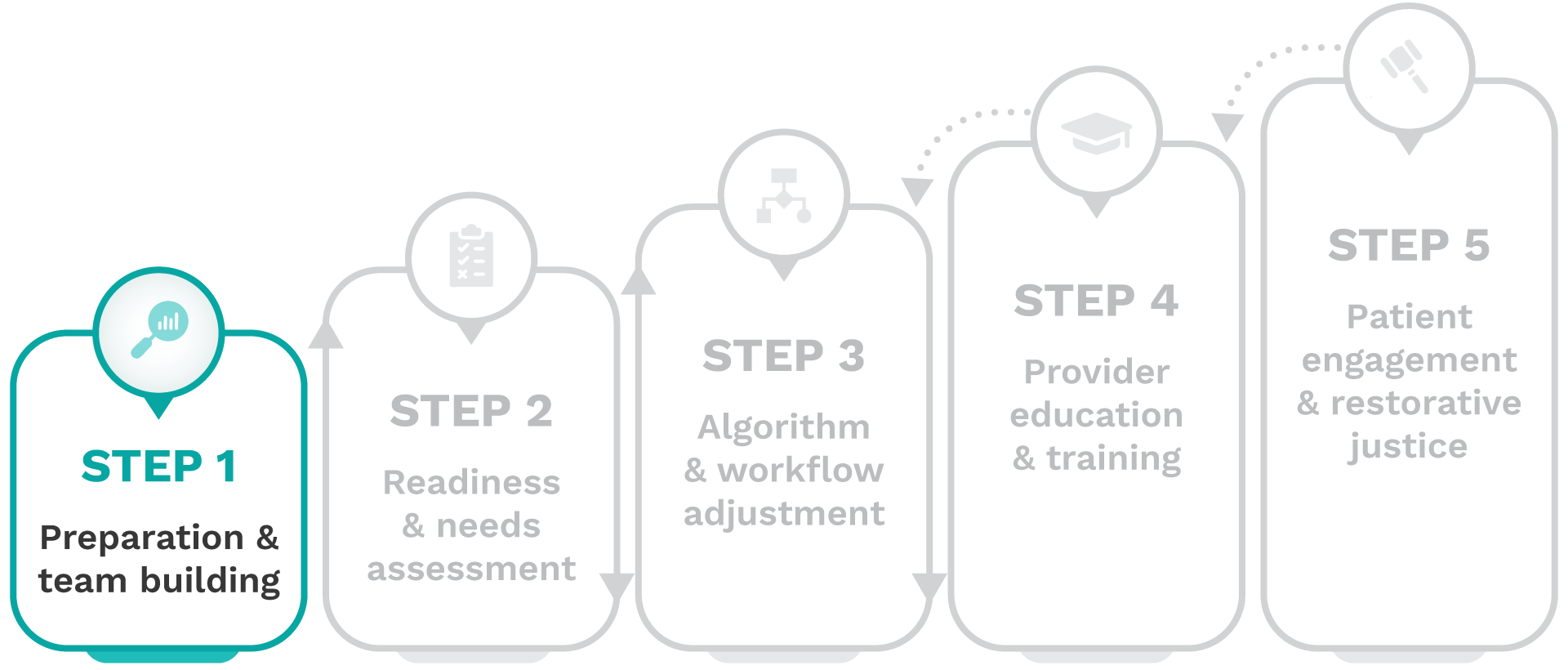

Removing harmful race-based clinical algorithms: A toolkit

Step 1-Preparation & team building

The goal of Step 1 is to assemble your team and create a strong foundation of shared knowledge and organizational alignment around the history and impact of harmful race-based clinical algorithms and the critical need to de-implement them.

Important stakeholders

When assembling your team, it’s important to bring together the right mix of expertise and perspectives to ensure a successful de-implementation process. Key stakeholders to consider include: executive champions, health equity leadership, clinicians and trainees, information technologists, qualitative and quantitative data scientists, and non-clinical roles like policy, operations, training, and education personnel, along with external experts and mentors including historians, social scientists, anthropologists, and patient advocacy groups.

Complete these activities

To achieve this goal, complete the following activities:

1. Explore toolkit resources

Review the overview guide and toolkit, including case studies and research spotlights depicting the use of race in clinical decision-making, the inequities minoritized patients face, and potential barriers and facilitators to de-implementation for your institution.

- Root of the problem: Medicine has historically treated white bodies as the default, while categorizing minoritized bodies as “other”—a concept known as racial essentialism.

- How it appears in practice: Race is sometimes still used as a biological proxy in clinical tools like eGFR (kidney function), VBAC (birth planning), and PFT (lung capacity) algorithms, despite no scientific basis.

- The impact on minoritized patients: These outdated tools delay care, limit access to treatment, and reinforce false ideas about biological differences between races.

- Unacceptable status quo: This practice perpetuates slavery-era science, like the use of spirometers to justify forced labor. Keeping these algorithms in place continues that legacy.

- Call to action: Shift toward race-conscious medicine by replacing race-based algorithms with evidence-based alternatives or shared decision-making approaches that center patient needs.

Discussing medical racism and algorithmic bias is challenging, often evoking discomfort, resistance, or uncertainty within your team. Real-world case studies offer a shared starting point to help teams learn the historical roots of race-based decision-making and align on the need for change.

- Historical roots of race-based hypertension treatment, to explore how race-based treatment guidelines have reinforced inequities, highlighting the need for race-conscious clinical approaches: View case study

- Race-conscious CDSS for equitable heart failure triage, to explore how a race-conscious clinical decision support system (CDSS) strategically uses race to address disparities in heart failure triage and guide equitable cardiology admissions: View case study

Align your team with shared definitions of health equity before you proceed:

Align your team with shared definitions of health equity before you proceed:

- Algorithm: Step-by-step procedures used for calculation, data processing, and automated reasoning.

- Inequity: Unfair or unjust distributions of resources across social, economic, environmental, and health care systems.

- Race-based medicine: The system by which research characterizing race as an essential, biological variable, translates into clinical practice, leading to inequitable care.

- Race-conscious medicine: Emphasizes racism, rather than race, as a key determinant of illness and health, encouraging providers to focus only on the most relevant data to mitigate health inequities.

- Race essentialism: The belief that socially constructed racial categories reflect “inherent” biological differences.

- Race-neutral: not based on people’s race or giving a special advantage to people of any race.

2. Identify a macro champion

Identify and engage a champion who demonstrates strong leadership and a personal commitment to promoting the institution’s de-implementation process.

3. Build your team

Build a team of all available stakeholders to participate in the de-implementation process, beginning with shared knowledge of the history and impact of race-based clinical algorithms in healthcare.

4. Consult external experts

Consult with external experts including patient advocacy groups, community representatives, historians, social scientists, and anthropologists to explore the historical and epidemiological context of the use of race, address the counter narrative, and highlight its impact on patient care experiences.

5. Gather provider input

Gather provider perspectives and feedback on how race modifiers are applied in clinical decision-making and resource allocation at the institution.

6. Educate your team

Use content from the toolkit to prepare and conduct educational sessions to enhance stakeholder knowledge, ensuring cultural and contextual applicability to the staff and patient population at your institution.

CERCA compiled a brief summary for the following algorithms: kidney function (eGFR), pulmonary function (PFT), and vaginal birth after cesarean section (VBAC). Use these summaries to support education and alignment by illustrating the historical context, clinical impact, and successful de-implementation strategies in practice.

Addressing the counter narrative

Resistance to change is natural, particularly when the topic is as sensitive as medical racism dating back to the slavery era. We suggest that resistance is addressed by finding common ground on the need for nuanced, individualized approaches to healthcare for all patients, with the agreement that a broader set of socioeconomic and environmental factors, including social determinants of health (SDOH), will provide more personalized care.

Here are the five key points of resistance you may encounter when discussing the de-implementation of harmful race-based clinical algorithms, along with the common ground that can be used to address them:

Some may argue that the inclusion of race in clinical decision-making is critical for providing tailored, individualized patient care. However, individualized care requires a race-conscious approach that uses only the most relevant, evidence-based factors to tailor treatment rather than relying on broad racial categories.

Both perspectives prioritize individualized care, where race is considered meaningfully alongside other clinical and social factors to improve accuracy and outcomes.

Some may argue that removing race adjustments could unintentionally worsen care by making clinical tools less precise. However, implementing evidence-based, race-conscious algorithms works to improve efficacy for all patients by using the most representative and clinically relevant variables.

Both perspectives seek to avoid unintended harm, and refining clinical tools with the most appropriate inputs helps prevent disparities while improving care for all patients.

The emphasis on race-neutral tools may be framed as driven by activism over evidence. However, a race-conscious approach does not call for the blanket removal of race in clinical decision-making, but instead incorporates the most relevant social and clinical factors based on research and practice.

The common ground is clear: prioritizing evidence-based medicine.

Skeptics suggest that implementing policies to redress historical inequities could overburden systems and lead to inequities for other patient populations. However, addressing inequities is not a zero-sum game; rectifying systemic bias enhances care for minoritized populations without diminishing the quality of care for others.

All parties want to ensure fair and effective healthcare delivery for all patient populations.

Calls may be made for additional research and updating, rather than removing, race-based clinical algorithms. However, when there is evidence of harm, the race-based clinical algorithm should be removed and replaced with an evidence-based, race-conscious alternative, whether it equitably utilizes race, is race-neutral, or means a more nuanced shared decision-making approach is considered best practice.

We all support and promote ongoing research to ensure that clinical practice evolves through continuous evaluation.

Next steps

Once you have completed these activities, your team will be equipped with foundational knowledge of how race-based clinical algorithms may harm your patients and why removing these algorithms is imperative for your organization. With your macro champion and team in place, you have laid the groundwork for collaborative efforts in subsequent steps.