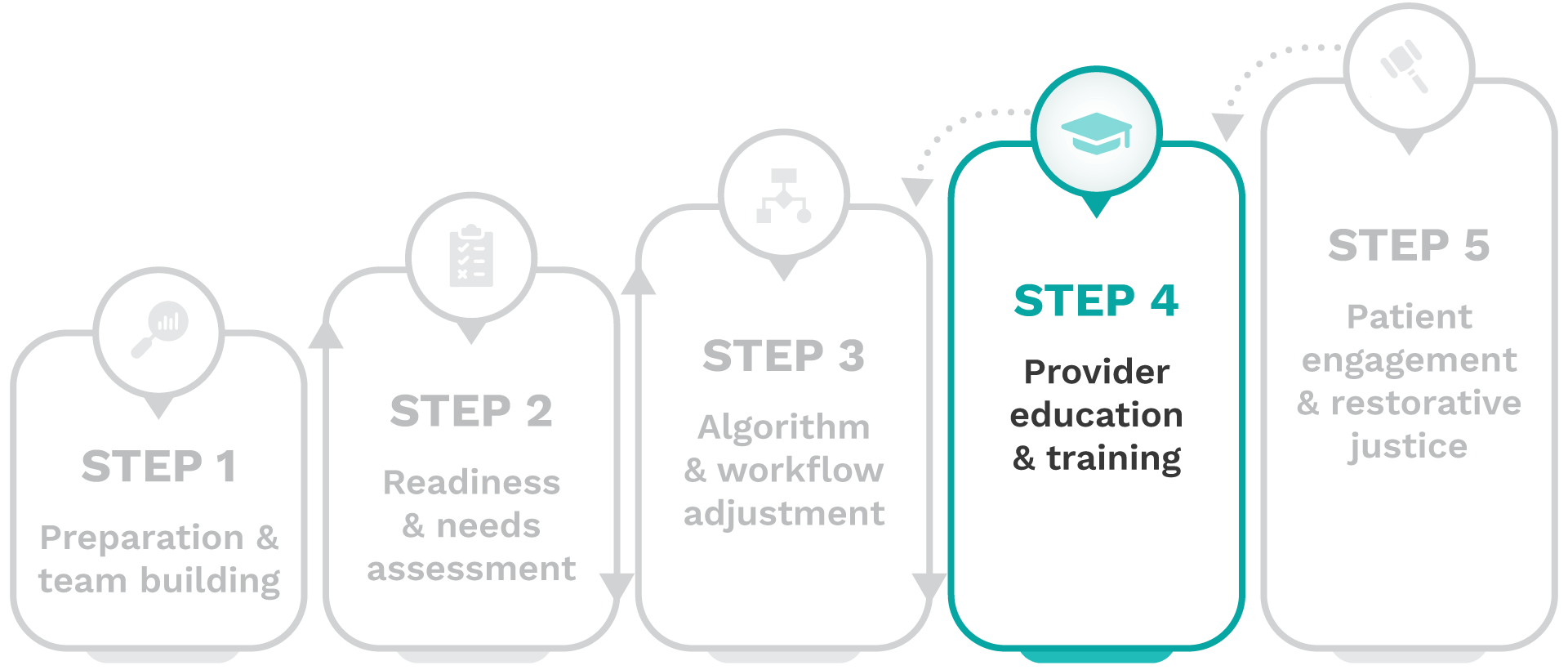

Removing harmful race-based clinical algorithms: A toolkit

Step 4-Provider education & training

In Step 4, you will equip your providers and trainees with the knowledge and skills they need to adopt race-conscious practices and implement changes in care delivery following the removal of harmful race-based clinical algorithms.

Important stakeholders

Training and education personnel, along with providers, students, and trainees involved in patient care and clinical decision-making, including physicians, physician assistants, nurses, nurse practitioners, clinicians, respiratory therapists, lab technicians, radiologists, other allied health professionals, to ensure comprehensive education regarding adjustments to algorithms and workflows.

Complete these activities

To achieve this goal, complete the following activities:

1. Fundraise for provider training

Fundraise to allocate dedicated resources to support the development, delivery, and maintenance of provider training and education initiatives.

There are payment and policy incentives aligned with de-implementing harmful race-based clinical algorithms which may help support fundraising efforts. Kidney disease management for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients insured by Medicare and Medicaid provides a key example of how this work can be integrated into CMS health equity plans and payment models:

- Inaccurate eGFR and Delayed Care: Race-based clinical algorithms, such as eGFR, have historically underestimated kidney disease severity in Black patients, delaying referrals for nephrology care and transplant evaluations.

- Equitable eGFR and Timely Referrals: De-implementing race-adjusted eGFR in favor of race-neutral calculations ensures more equitable disease staging, leading to earlier and more appropriate referrals for dialysis and transplantation in Black patients.

- CMS Payment Incentives for Equity: This shift aligns with CMS’s focus on equitable access to treatment and is reinforced by payment models such as the End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Treatment Choices (ETC) and Increasing Organ Transplant Access (IOTA) models.

- ETC and IOTA Models: The ETC model encourages greater use of home dialysis and kidney transplants, while the IOTA model incentivizes higher kidney transplant rates, particularly for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients. The IOTA model offers up to $8,000 per kidney transplant performed on a Medicare fee-for-service patient and applies a 1.2 score multiplier for transplants in socioeconomically disadvantaged patients.

- Health Equity Plans as a Requirement: Hospitals participating in the IOTA model must develop a health equity plan outlining strategies to increase access to transplantation for underserved populations.

- Improved Outcomes and Financial Alignment: By adopting race-neutral eGFR calculations, healthcare providers can improve patient outcomes, ensure timely referrals, and increase access to kidney transplantation—all while aligning with CMS health equity requirements and maximizing financial incentives under the ETC and IOTA models.

2. Deliver bias training

Deliver provider training on implicit bias, the unique considerations for diagnostic and prognostic algorithms, and strategies for addressing the counter narrative promoting the use of race in clinical decision-making.

To address provider unlearning, consider framing discussions around the difference between intent and impact to help providers learn how well-intended practices can still perpetuate bias—fostering openness to change and deeper engagement.

- Intent vs impact in medical algorithms: View case study

3. Develop workflow update materials

Develop training and education materials to detail the changes in care delivery workflows following harmful race-based clinical algorithm de-implementation.

4. Conduct workflow training sessions

Conduct grand rounds and inservice presentations; develop e-learning modules and online courses; host workshops and discussion forums, that deliver training and education to providers, students, and trainees involved in adjusted clinical workflows.

5. Illustrate impact with case studies

Incorporate case studies and scenarios that illustrate the impact algorithm and workflow modifications have on minoritized populations into provider education and training.

Countering established clinical practice guidelines can be challenging and intimidating. To engage providers effectively, consider presenting a critical analysis of the JHC 8 Guidelines to demonstrate how race-based adjustments can perpetuate bias and how evidence-based alternatives can improve care.

- Examining the use of race in clinical decision-making: hypertension prescription management guidelines example: View case study

6. Refine case studies with patients

Use insights from patients and advisory groups to refine case studies and scenarios, ensuring provider training reflects diverse perspectives and community needs.

7. Identify additional training needs

Identify additional training needs and educational opportunities for medical students, trainees, and providers of all types utilizing algorithms in clinical decision-making.

Addressing the counter narrative

Resistance to change is natural, particularly when the topic is as sensitive as medical racism dating back to the slavery era. We suggest that resistance is addressed by finding common ground on the need for nuanced, individualized approaches to healthcare for all patients, with the agreement that a broader set of socioeconomic and environmental factors, including social determinants of health (SDOH), will provide more personalized care.

Here are the five key points of resistance you may encounter when discussing the de-implementation of harmful race-based clinical algorithms, along with the common ground that can be used to address them:

Some may argue that the inclusion of race in clinical decision-making is critical for providing tailored, individualized patient care. However, individualized care requires a race-conscious approach that uses only the most relevant, evidence-based factors to tailor treatment rather than relying on broad racial categories.

Both perspectives prioritize individualized care, where race is considered meaningfully alongside other clinical and social factors to improve accuracy and outcomes.

Some may argue that removing race adjustments could unintentionally worsen care by making clinical tools less precise. However, implementing evidence-based, race-conscious algorithms works to improve efficacy for all patients by using the most representative and clinically relevant variables.

Both perspectives seek to avoid unintended harm, and refining clinical tools with the most appropriate inputs helps prevent disparities while improving care for all patients.

The emphasis on race-free tools may be framed as driven by activism over evidence. However, a race-conscious approach does not call for the blanket removal of race in clinical decision-making, but instead incorporates the most relevant social and clinical factors based on research and practice.

The common ground is clear: prioritizing evidence-based medicine.

Skeptics suggest that implementing policies to redress historical inequities could overburden systems and lead to inequities for other patient populations. However, addressing inequities is not a zero-sum game; rectifying systemic bias enhances care for minoritized populations without diminishing the quality of care for others.

All parties want to ensure fair and effective healthcare delivery for all patient populations.

Calls may be made for additional research and updating, rather than removing, race-based clinical algorithms. However, when there is evidence of harm, the race-based clinical algorithm should be removed and replaced with an evidence-based, race-conscious alternative, whether it equitably utilizes race, is race-neutral or race-free, or means a more nuanced shared decision-making approach is considered best practice.

We all support and promote ongoing research to ensure that clinical practice evolves through continuous evaluation.

Clinical Outcome Measures: eGFR

PRIORITIZED TOP 5: Primary

- Referral or current care provided by nephrologist

- Referral or waitlist status for kidney transplantation

- CKD stage reclassification Utilization of

- medications to slow CKD progression

- Prevalence of CKD by stage

Clinical Outcome Measures: PFT

PRIORITIZED TOP 5: Primary

- Diagnosis of lung disease

- Referral to pulmonologists

- Prevalence of obstructive & restrictive pulmonary disease, overall & by severity

- Prescription of medications for lung diseases as recommended by COPD & asthma guidelines

- Reclassification of lung disease severity

Clinical Outcome Measures: VBAC

PRIORITIZED TOP 5: Primary

- VBAC rates

- TOLAC rates

- Postpartum complication rates

- Vaginal birth rate

- Primary and repeat cesarean rates

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

As a clinician, you play a crucial role in de-implementation efforts. Beyond delivering patient care, you will help educate patients on any changes to care plans and guide them through the impact on their treatment. Clinicians are key throughout this process. Your expertise can help:

- Provide input on the use of race in clinical decision-making (Step 1).

- Give feedback on training to support the readiness assessment (Step 2).

- Champion de-implementation and refine care strategies (Step 3).

- Disseminate updates to colleagues (Step 4).

- Support patient education and engagement (Step 5).

Your participation is invaluable in shaping at your institution’s de-implementation effort.

Staffing constraints, resource limitations, and provider burnout are common barriers to successful de-implementation. Experts recommend “alignment, not extra effort”; this means leveraging existing initiatives, integrating with institution-wide standardization efforts, and forming well-structured subcommittees with clear tasks can help streamline the process. Additionally, scheduling meetings at clinician-friendly times reduces disruptions and minimizes the extra workload required for de-implementation.

Practice guidelines continuously evolve as new evidence emerges, and recent research indicates that race-based algorithms are no longer the gold standard in many cases. Additionally, Section 1557 of the ACA mandates non-discrimination based on race and other protected characteristics, including clinical decision-making tools. By May 2025, federally funded health systems must identify decision support tools that rely on protected traits and take steps to mitigate potential discrimination. As a result, de-implementing harmful algorithms has become a key priority for health systems nationwide, paving the way for more equitable and effective patient care.

Training requirements will vary by institution, but experts from organizations that have successfully de-implemented one or more harmful race-based clinical algorithms recommend implicit bias training and culturally responsive communication as particularly valuable. If your institution already offers education related to health equity, these topics can be seamlessly integrated into existing programs.

For those involved in curriculum development, additional training can include:

- The history of harmful race-based algorithms and the development of race-conscious alternatives.

- Effective patient education strategies to support informed decision-making (see Step 5).

Aligning training with institutional priorities ensures a streamlined approach to de-implementation.

Just as race-based algorithms require de-implementation to address bias, AI tools in healthcare must be carefully monitored to ensure they don’t perpetuate racial inequities. Under ACA Section 1557, AI is subject to the same non-discrimination requirements as other clinical tools.

A key concern is the “garbage in, garbage out” problem—AI models are only as reliable as the data they are trained on. To prevent AI from amplifying the issues seen in race-based clinical algorithms, healthcare organizations should:

- Assess AI tools for reliance on race-based assumptions

- Scrutinize training data for bias and gaps

- Engage diverse stakeholders in model development and monitoring

De-implementing harmful race-based algorithms sets the stage for ensuring AI models are fair, effective, and compliant with non-discrimination policies.

Discussing race in patient care can be challenging and, at times, controversial. Patient engagement should begin once institutional support for de-implementation is secured and foundational work is in place. Keeping the focus on shared goals can help navigate these conversations, and frameworks like Healing ARC may also provide useful guidance.

This can be achieved by:

- Engaging patient advocacy groups in the de-implementation process.

- Using shared decision-making strategies to empower individual patients.

Because de-implementation is highly contextual, your expertise as a provider is vital in shaping strategies that fit your practice and patient population.

As a clinician, you play a critical role in de-implementation efforts. Start by building awareness—actively assess whether race-based assumptions have shaped the algorithms or paradigms in your field, and stay informed on emerging data, particularly regarding inequitable outcomes.

If possible, engage with patient advocacy efforts at your institution and help amplify concerns, ensuring that patient voices are heard and that delivering appropriate care remains a priority in clinical decision-making.

The bottom line is simple: Always ask “why” whenever race is used as input for a decision.

Taking steps to provide the most appropriate care for all of your patients can help reduce legal liability risks. However, this is not legal advice—consult your institution’s legal and compliance teams for guidance. In your discussions about liability, consider the following:

- Legal and ethical risk: Continuing to use race-based algorithms despite evidence of harm may increase liability if they contribute to inequitable health outcomes.

- Compliance: National guidelines, including NKF-ASN recommendations on eGFR and CMS health equity requirements, support race-conscious approaches.

- Anti-discrimination protections: Section 1557 of the ACA prohibits racial bias in healthcare, and the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) requires that clinical decision-making comply with these protections, making harmful race-based algorithms a potential legal vulnerability.

- Patient trust and proactive change: Due diligence and adherence to best practices when addressing bias in clinical algorithms can foster patient trust, improve satisfaction with care, and strengthen legal defense in cases of alleged discrimination.

There is an “Additional resources” section at the bottom of the toolkit’s landing page – check this out fore more information, including the inaugural CERCA report, NYC Health Department Race to Justice Glossary, and more.

You can also access a comprehensive list of additional resources linked at the bottom of every page of the toolkit – refer to this resource for our recommendations!

Next steps

Once you have completed these activities, your providers will have increased knowledge and confidence in race-conscious practices and updated clinical workflows, allowing for improved care delivery and patient outcomes in real-time.