Japan National Companion Guide

Pursue DHT market access in Japan

Feedback

These pathways are constantly evolving. Work with us to keep them up to date by providing suggestions and feedback.

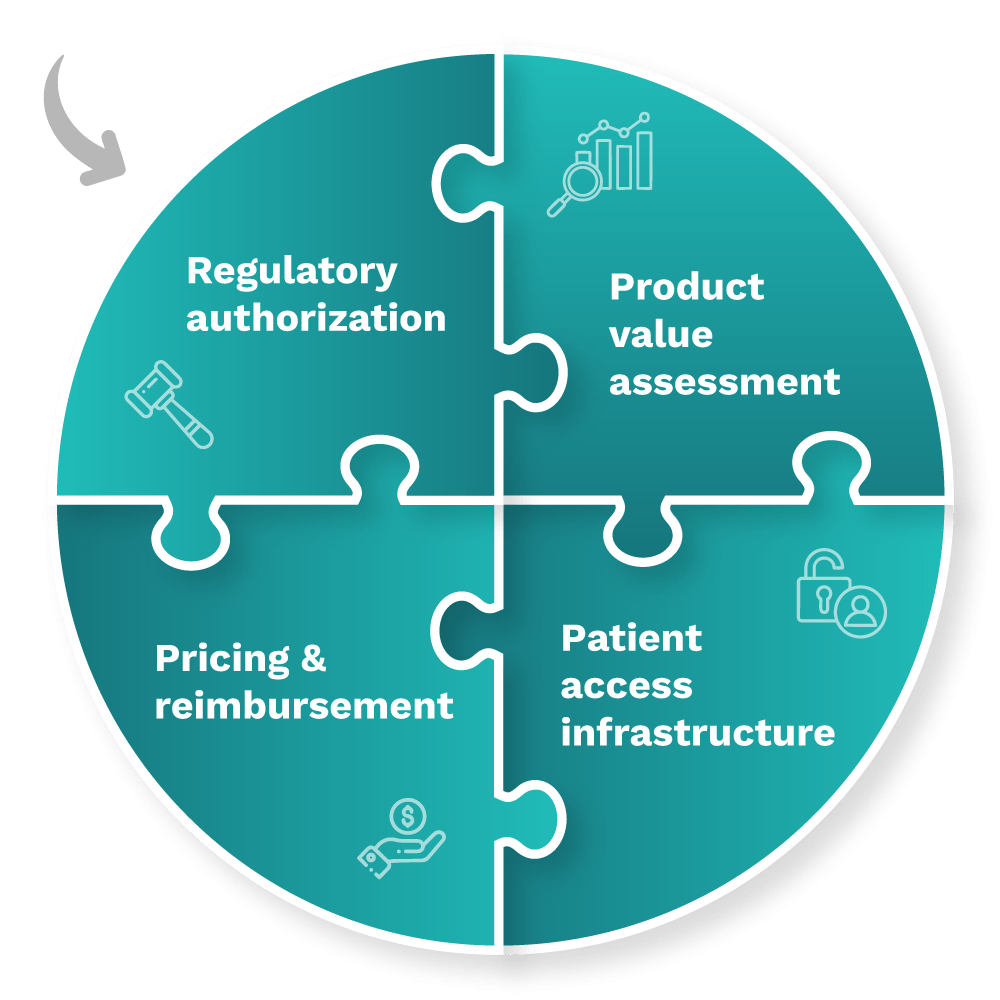

In Japan, digital health technology (DHT) product regulatory authorization, value assessment, and pricing and reimbursement are conducted at the national level. However, developers often pursue patient access infrastructure via local routes.

Use the resources below to explore pathways for scalability and to start planning your regulatory strategy to bring your DHT to market in Japan.

What is a policy “full-stack”?

A policy “full-stack” provides a structured approach for integrating digital health technologies (DHT) into national healthcare systems.

Components of a comprehensive national policy for DHTs

Regulatory authorization

Product value assessment

Patient access infrastructure

Pricing & reimbursement

Read more about the core elements of a national policy “full-stack” approach.

This guide reflects current information as of 15 October 2024. National regulations and practices are subject to change and evolve, so developers are encouraged to regularly consult relevant agency websites for the latest information.

Explore DHT patient access and product scalability pathways

Begin your assessment of Japan’s routes to DHT patient access by reviewing this snapshot, which offers insights into the potential patient access and product scalability pathways available for remote patient monitoring (RPM), digital diagnostic (Dx), digital therapeutics (DTx), and clinical decision support (CDS) products.

Navigate national pathways for DHT patient access

And then, use this flowchart to help you navigate Japan’s national pathways for DHT market access, guiding you through key steps in regulatory review, product assessment, pricing, reimbursement, and patient access. Aligned with the four core elements of a national policy “full-stack,” it focuses on national pathways and does not provide detailed insights on local routes.

As you move through the flowchart, you’ll see where developers need to generate or present clinical evidence to demonstrate each product’s safety, efficacy, and impact. “Clinical evidence evaluation” refers to a review of published data, while “clinical investigation” highlights when you may need to conduct a study to verify your product’s safety and performance.

Use this flowchart to stay informed at each stage and understand what’s expected to bring DHTs to patients in Japan.

This flowchart:

- Provides a sample of important steps along the pathway to patient access—not including post-market assessment pathways—and is subject to change. Other exclusions may exist.

- References DHT products that qualify as a medical device. DHT products that are not recognized as medical devices are not represented in this flowchart.

- Focuses primarily on national pathways and does not provide detailed insights on local case-by-case routes.

- Identifies certain opportunities to generate clinical evidence evaluations and investigations but does not incorporate health economic outcomes research (HEOR).

- Does not include specific timelines and is not intended to indicate how long or when steps are conducted.

National policy “full-stack” components

As the snapshot indicates, DHT product regulatory authorization, value assessment, and pricing and reimbursement in Japan are conducted at the national level.

Click below for more insights

- DHTs encompass a wide range of intended uses and risk levels. In Japan, products that perform remote patient monitoring (RPM), digital diagnostics (Dx), digital therapeutics (DTx), and clinical decision support (CDS) that qualify as medical devices may be classified into Class II or III of the four available product categories: Class I, II, III, or IV.

- Medical devices that are unlikely to affect human life or health, even if functional impairment occurs (Class I equivalent), are excluded from the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Act.

- Classification as a Class II or III medical device is determined based on the extent to which the product contributes to decisions on treatment policies, etc., and the risks involved in the event of a malfunction.

- The Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) offers an optional consultation for determining whether or not software should be considered Software as a Medical Device (SaMD).

- Medical devices are regulated and classified in Japan based on product risk. Helpful legislative milestones include:

- In 2014, the “Act on Securing Quality, Efficacy and Safety of Pharmaceuticals, Medical Devices, Regenerative and Cellular Therapy Products, Gene Therapy Products, and Cosmetics” (“Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Act”) came into effect.

- In 2015, PMDA introduced the Sakigake system, allowing review time to be cut in half (from 12 months to 6 months) for designated drugs/devices, including digital health technologies.

- In 2017, the Conditional Early Approval System was implemented, allowing for early approval of highly needed innovative medical devices and speeding up the practical application of drugs.

- In 2023, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) unveiled its second SaMD strategy, “Digital Transformation Action Strategies (DASH) for SaMD 2,” building upon the former framework, “DASH for SaMD,” that was established in 2020. Implementation of this two-stage approval system went into effect in 2024.

- In Japan, the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) work together during the device assessment process.

- In Japan’s two-stage approval system, initial approval may be granted for a limited scope of intended uses based on how well the software performs in tests, even if the ultimate clinical significance has not yet been fully established. Second-stage approval can be obtained after more evidence and data is gathered from real-world use.

- PMDA provides manufacturers with a broad range of services. In January 2024, PMDA released its draft mid-term plan, covering the period from JFY 2024 to JFY 2028.

- This plan introduces a target review timeframe of 6 months for SaMD products undergoing priority review.

- PMDA is setting out to restructure its organization to incorporate a department dedicated to SaMD review and establish a new consultation category for improved guidance and support.

- In Japan, the National Health Insurance (NHI) system is responsible for reimbursement decision-making. Once a medical device or SaMD receives approval from PMDA, it must undergo a separate assessment for reimbursement under NHI.

- This assessment evaluates the technology’s clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and potential to improve patient outcomes compared to existing treatments.

Curated overview of clinical evidence requirements and practices

Regardless of the class of the medical device, the Japanese Marketing Authorization Holder (MAH) of such a device must ensure efficacy, safety, and quality based on the evidence before submission.

Click below for more insights

In Japan, PMDA distinguishes between five types of medical device applications in their review process:

- New medical devices.

- Improved medical devices (with clinical data).

- Improved medical devices (without approval criteria, without clinical data).

- Generic medical devices (without approval criteria, without clinical data).

- Generic medical devices (with approval criteria, without clinical data).

MHLW’s Next Generation Medical Device Evaluation Index specifically addresses evaluation indicators for medical device programs with behavior change. Publication highlights include:

- In establishing a control group, the need for standard treatment, existing behavior-altering medical device programs, sham applications, etc., should be appropriately considered, and evidence of clinical efficacy should be established.

- If it is necessary to evaluate the persistence of efficacy, an appropriate observation period should be established.

- Widely recognized standard objective indicators should be used to establish evaluation items whenever possible. Subjective indicators may be used depending on the target disease and clinical positioning of the device with behavior change.

- Matters to consider that could affect clinical outcomes:

- Influence of race and cultural background: Even for products that have been used overseas and have clinical trial results, clinical trials should be conducted in Japan as necessary, taking into consideration that not only racial differences but also cultural backgrounds including religion, moral values, and living environment may affect efficacy in medical device programs involving behavioral changes. It is also desirable to evaluate the effects of generational differences and the effects of regional characteristics.

- Influence of the timing of development and the age at which the clinical trials were conducted: The impact of the evaluated historical background on efficacy and safety should be evaluated. For example, when a product developed ten years ago is submitted for approval, or when disease guidelines, etc., are revised, it is necessary to reevaluate the impact on performance and the clinical positioning of the device in question.

- Impact on patient adherence: Some behavior change medical device programs are considered to be effective with continued use, and therefore, factors that may affect the rate of continued use may also affect the clinical outcome of the device in question. For example, the following items may be mentioned:

- Graphical user interface, including fonts and background colors.

- Representation of messages to be output.

- Matters that depend on preferences, such as dialects, characters, etc.

- Safety considerations: For products that may present clinically unacceptable hazards, robust outcomes and risk assessments are required. It is important to consider the risk of inappropriate interventions (e.g., excessive exercise for the elderly, inappropriate dietary guidance for patients with dietary restrictions, etc.) for patients and others for whom the product is indicated, and to conduct a risk assessment that also takes into account product specifications and methods of alerting the public.

PMDA accepts and reviews foreign clinical data of medical devices that have applied for marketing approval in Japan. Japan has specific requirements for the acceptance of foreign data. Handling of clinical data for medical devices conducted in foreign countries (1997) and Handling of clinical study data on medical devices which was carried out in foreign countries (2006) provide further insights, in addition to PMDA’s FAQ page.

Broadly, Japan may accept foreign data when:

- Methods for the study and evaluation are congruent with Japanese standards.

- Studies were conducted by qualified researchers at reliable medical institutions.

- Studies were conducted in accordance with international standards on appropriate practices [i.e., Declaration of Helsinki, Japanese good clinical practice (GCP) regulations] and GCP standards in the source country should be equal to or exceeding Japanese guidelines. If there are differences, they must be enumerated and explained.

- The raw data is accessible if needed and endorsed (signed) by the responsible investigator.

Clinical data and related materials should be accompanied by an accurate Japanese translation, as well as the qualifications of the translator.

Engaging with national regulators

There are two regulatory authorities responsible for the regulation of medical devices in Japan: the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) and the Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Agency (PMDA). MHLW is responsible for administrative actions such as issuing guidance or decisions regarding product approval pursuant to the PMD Act, as well as judgment on whether a product is considered as a medical device. PMDA undertakes product reviews and post-market safety measures.

Any company intending to manufacture and distribute drugs or medical devices in Japan is required to submit an Application for Accreditation of Foreign Manufacturers. Information about the regulatory submission process is available on PMDA’s Regulations and Approval/Certification of Medical Devices page.

Certain Class II and Class III devices with established certification standards must be certified by a registered body; a list of registered certification bodies is available in Japanese. Additionally, consultation meetings are available for products which require MHLW approval (certain Class II and Class III; all Class IV).

PMDA provides information on standard review timelines (available only in Japanese):

- On the Standard Review Timeline for New Medical Devices.

- On the Standard Review Timeline for Improved Medical Devices (with clinical data).

- On the Standard Review Timeline for Improved Medical Devices (without clinical data).

PMDA’s Profile of Services provides a variety of insights on the agency’s work, including review times for medical devices (in English).

Medical devices that require “Approval of the MHLW” have to first be evaluated for safety and efficacy by the PMDA. Regulatory requirements for individual products to be approved are assessed on a case-by-case basis and answered in the PMDA’s face-to-face consultation meetings (fees applicable).

PMDA offers consultations to give guidance and advice on clinical trials of drugs, medical devices, and cellular and tissue-based products, as well as on data for regulatory submissions. PMDA also provides prior assessment consultations, in which its reviewers evaluate data on the quality, efficacy, and safety of a product in the pre-submission stage and the consultation process constitutes part of the review of the product once the application is submitted.

To achieve realization of innovative drugs, medical devices, and regenerative medical products, PMDA launched the Regulatory Science (RS) Consultations, mainly for universities, research institutions, and venture companies that possess promising “seed-stage” research or technologies. In the consultation, advice will be provided on the tests needed in the early product development stage and the necessary clinical trials, which are considered to play a part in important functions to promote creation of innovative products in Japan.

PMDA also offers a consulting service specific to software as a medical device (SaMD). More information about the service, and application procedures, are found on SaMD Unified Consultation Desk (Comprehensive Medical Device Program Consultation) [in Japanese].

An additional service to consider is MEDISO (Medical Innovation Support Offices), which is sponsored by MHLW. MEDISO provides support for business ventures, academia, and individuals intending to put into practical use medicines, medical devices, and regenerative medicinal products.

In order to market medical devices in Japan, a foreign manufacturer has to obtain approval/certification or submit notification, depending on the classification, pursuant to the PMD Act, through a Japanese Marketing Authorization Holder (J-MAH) or a Japanese manufacturer appointed by such a foreign manufacturer. While PMDA does not provide a specific list of J-MAHs, they do provide links to Japan’s pharmaceutical and medical device manufacture associations, to which a J-MAH must belong.

Japan’s Pharmaceutical Affairs Law requires all forms related to the marketing application to be submitted in Japanese.

Glossary of terms

- Approval criteria

- Certification criteria

- Conditional approval system

- Controlled medical device

- General medical device

- Japanese Medical Device Nomenclature (JMDN)

- Medical devices

- Post-Approval Change Management Protocol (PACMP) for Medical Devices

- Priority review for specific uses

- Review guidelines

- SAKIGAKE Designation System

- Specially-controlled medical device

- Specially-designated medical devices requiring maintenance

Approval criteria

Criteria compliance which is assessed for regulatory approval of medical devices. “Approval criteria, composed of ISO [International Organization for Standardization] or IEC [International Electrotechnical Commission] standards, etc., in principle, are intended for products for which no clinical data are required to be submitted.”

Source: PFSB Notification

Certification criteria

Criteria for medical devices, for which compliance of medical devices is assessed by registered certification bodies that review applications of the devices. This criteria is specified by the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Source: PMDA

Conditional approval system

Process that accelerates approval of medical devices of high clinical needs by balancing pre- and post-market requirements, based on the lifecycle management of the medical device.

Source: PMDA

Controlled medical device

Refers to medical devices, other than specially-controlled medical devices, designated by the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare, after seeking the opinion of the Pharmaceutical Affairs and Food Sanitation Council, as devices requiring proper management due to their significant potential risk to human life and health in the event of a side effect or malfunction occurring.

General medical device

Refers to medical devices, other than specially-controlled medical devices and controlled medical devices, designated by the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare, after seeking the opinion of the Pharmaceutical Affairs and Food Sanitation Council, as devices with little potential risk to human life and health in the event of a side effect or malfunction occurring.

Japanese Medical Device Nomenclature (JMDN)

Nomenclature originally created on the basis of the 2003 version of the Global Medical Device Nomenclature (GMDN) and implemented in 2005. Each medical device is identified by the JMDN. The JMDN includes the device’s general name, definition, JMDN code, risk-based classification, and classification rule based on a Global Harmonization Task Force (GHTF) document titled “Principles of Medical Devices Classification.”

Source: PMDA

Medical devices

Appliances or instruments, etc. which are intended for use in the diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of disease in humans or animals, or are intended to affect the structure or functioning of the bodies of humans or animals (excluding regenerative medicine products), and which are specified by a Cabinet Order.

Post-Approval Change Management Protocol (PACMP) for Medical Devices

Protocol which enables continuous improvements through a product’s lifecycle.

Source: PMDA

Priority review for specific uses

Designation of “Specific use product” for highly unmet medical needs (e.g., pediatric use). Priority review and other supportive measures are applied to designated products for specific use.

Source: PMDA

Review guidelines

Guidelines specified by the MHLW which describe the major technical requirements and/or the acceptance criteria, etc. necessary to evaluate the safety and efficacy of medical devices, although no specific performance limits are determined for each technical requirement.

Source: PMDA

SAKIGAKE Designation System

System for promoting R&D in Japan that is aimed at early practical application for innovative pharmaceutical products, medical devices, and regenerative medicines.

Source: MHLW

Specially-controlled medical device

Medical devices designated by the MHLW, after seeking the opinion of the Pharmaceutical Affairs and Food Sanitation Council, as those requiring proper management due to their significant potential risk to human life and health in the event of a side effect or malfunction occurring (limited to cases where they are used appropriately in compliance with the appropriate purpose of use).

Specially-designated medical devices requiring maintenance

Medical devices designated by the MHLW, after seeking the opinion of the Pharmaceutical Affairs and Food Sanitation Council, as those requiring special knowledge and skills for their maintenance, inspection, repair, and other related work, due to their significant potential risk to the diagnosis, treatment or prevention of disease in the event of failure to provide such proper maintenance.

Acknowledgements

DiMe thanks the following organizations and individuals for reviewing components of the Japan National Companion Guide, Flowchart, and Snapshot:

- D-Health Consulting

- Kenichiro Nishii, Software Regulation Co., Ltd. (former CureApp)

- Eiji Takeda, Software Regulation Co., Ltd. (former CureApp)

- Naoyuki Kanda, Astellas Pharma Inc.