United States National Companion Guide

Pursue DHT market access in the United States

Feedback

These pathways are constantly evolving. Work with us to keep them up to date by providing suggestions and feedback.

In the United States, digital health technology (DHT) product regulatory authorization is conducted at the national level. However, developers often pursue product value assessment, pricing and reimbursement, and patient access infrastructure via local routes.

Use the resources below to explore pathways for scalability and to start planning your regulatory strategy to bring your DHT to market in the United States.

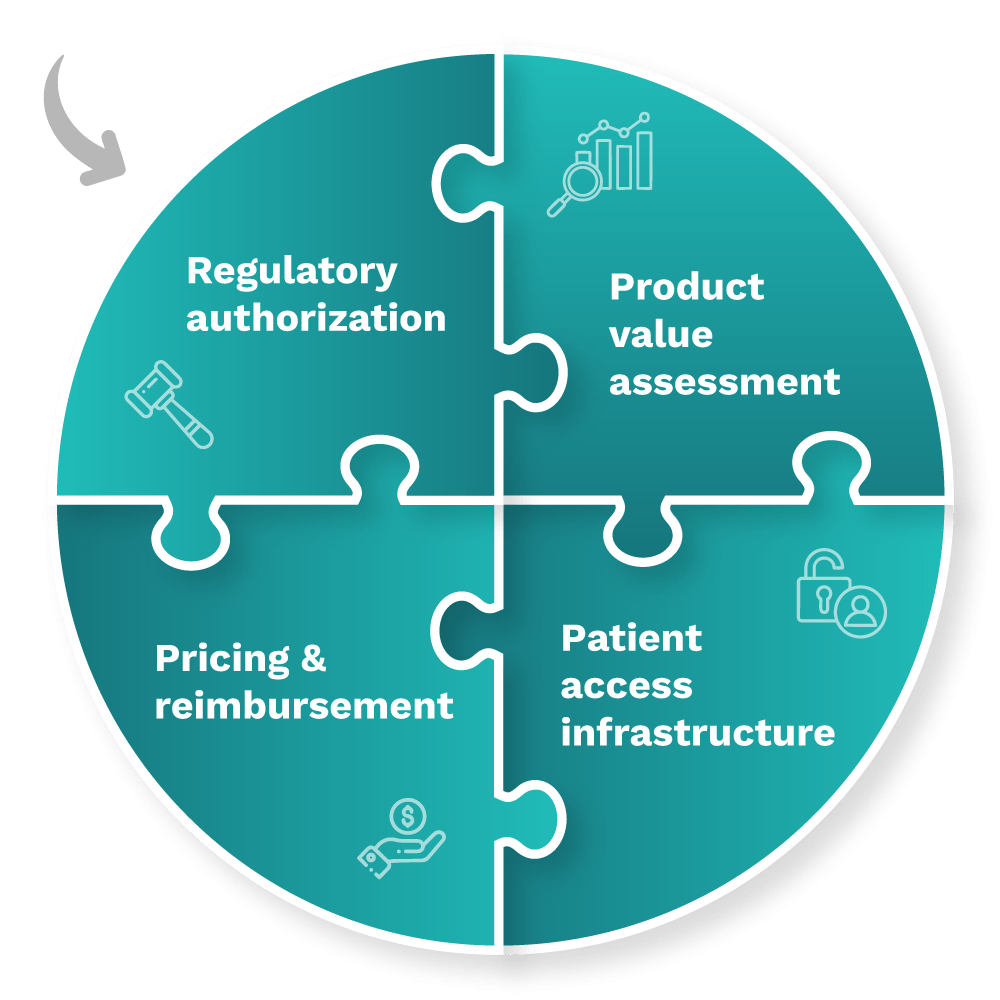

What is a policy “full-stack”?

A policy “full-stack” provides a structured approach for integrating digital health technologies (DHT) into national healthcare systems.

Components of a comprehensive national policy for DHTs

Regulatory authorization

Product value assessment

Patient access infrastructure

Pricing & reimbursement

Read more about the core elements of a national policy “full-stack” approach.

This guide reflects current information as of 15 October 2024. National regulations and practices are subject to change and evolve, so developers are encouraged to regularly consult relevant agency websites for the latest information.

Explore DHT patient access and product scalability pathways

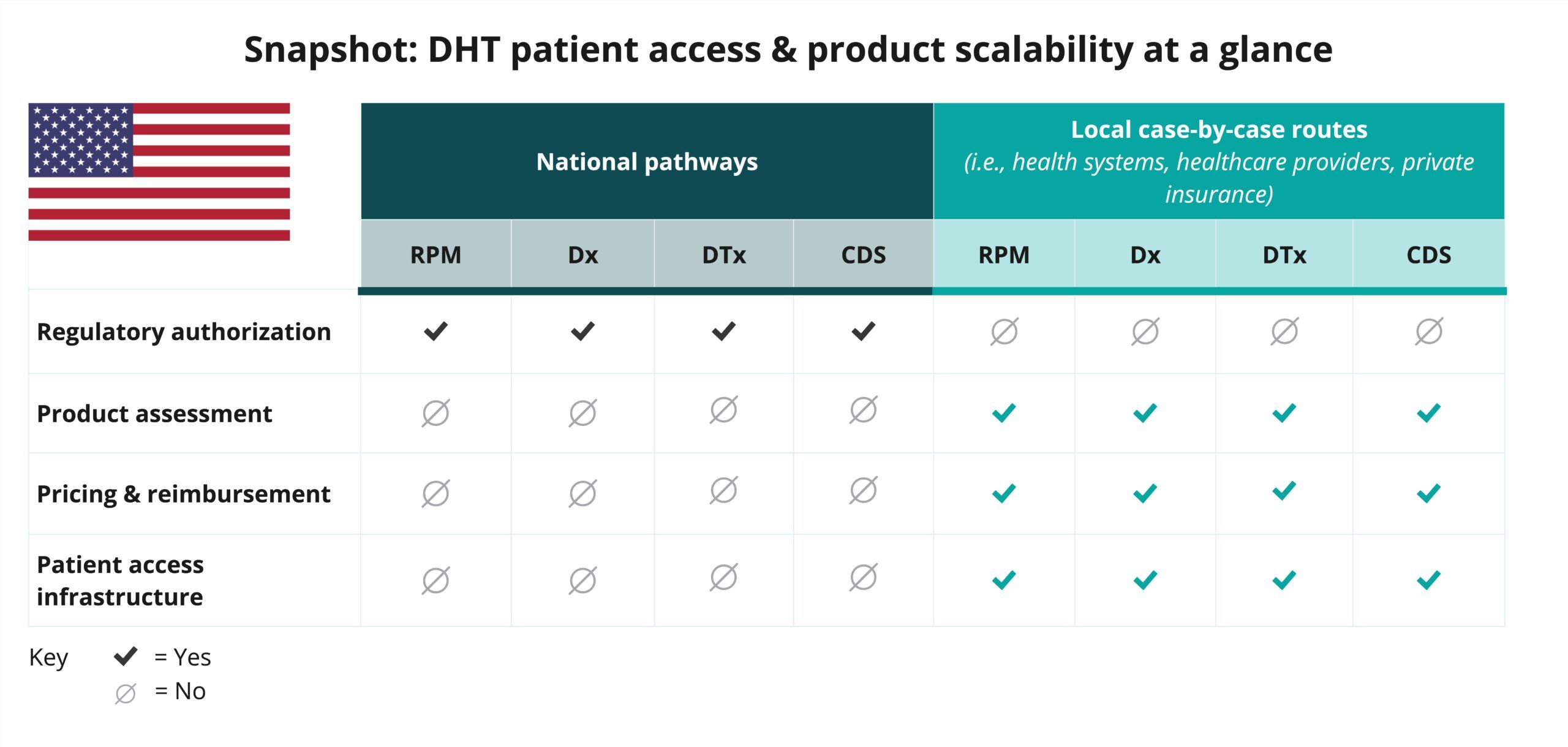

Begin your assessment of the United State’s routes to DHT patient access by reviewing this snapshot, which offers insights into the potential patient access and product scalability pathways available for remote patient monitoring (RPM), digital diagnostics (Dx), digital therapeutics (DTx), and clinical decision support (CDS) products.

Navigate national pathways for DHT patient access

And then, use this flowchart to help you navigate the United States’s national pathways for DHT market access, guiding you through key steps in regulatory review, product assessment, pricing, reimbursement, and patient access. Aligned with the four core elements of a national policy “full-stack,” it focuses on national pathways and does not provide detailed insights on local routes.

As you move through the flowchart, you’ll see where developers need to generate or present clinical evidence to demonstrate each product’s safety, efficacy, and impact. “Clinical evidence evaluation” refers to a review of published data, while “clinical investigation” highlights when you may need to conduct a study to verify your product’s safety and performance.

Use this flowchart to stay informed at each stage and understand what’s expected to bring DHTs to patients in the United States.

This flowchart:

- Provides a sample of important steps along the pathway to patient access—not including post-market assessment pathways—and is subject to change. Other exclusions may exist.

- References DHT products that qualify as a medical device. DHT products that are not recognized as medical devices are not represented in this flowchart.

- Focuses primarily on national pathways and does not provide detailed insights on local case-by-case routes.

- Identifies certain opportunities to generate clinical evidence evaluations and investigations but does not incorporate health economic outcomes research (HEOR).

- Does not include specific timelines and is not intended to indicate how long or when steps are conducted.

National policy “full-stack” components

As indicated in the snapshot, DHT product regulatory authorization in the United States is conducted at the national level.

Click below for more insights

- While some digital health technologies (DHTs) in the United States may be subject to regulation as a medical device, others may not be.

- Products that meet the definition of a medical device in the United States are categorized based on risk, not product type. DHTs that qualify as medical devices may be classified into one of three categories: Class I, II, or III.

- Most clinical decision support (CDS) products do not meet the definition of a medical device in the United States. It is important for developers to clearly identify when a product is in fact a CDS product, versus a product that qualifies in another category that meets the definition of a medical device.

- Developers must be familiar with relevant regulations and are encouraged to communicate with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to understand how their device will be classified and regulated based on risk.

- In the United States, pricing, reimbursement, patient access, and product assessment by purchasers are primarily conducted at the local level on a case-by-case basis (i.e., private insurers, health systems, healthcare providers, and employers).

Curated overview of clinical evidence requirements and practices

The FDA applies “least burdensome” principles to its clinical data requirements. The FDA does not provide prescriptive guidance regarding what is needed to prove effectiveness. Whereas most products in the United States that pursue the FDA’s De Novo pathway require clinical data, only 10-15% of products that pursue the 510(k) process require clinical data.

Click below for more insights

- 510(k) Pathway

- If the intended use and technological characteristics of a device are substantially similar to its predicate device, robust non-clinical safety and efficacy data may be sufficient for approval; however, clinical data may be required to prove substantial equivalence (SE).

- Any clinical data submitted should comply with standards for valid scientific evidence (21 CFR 860.7(c)(2)) and may include pre- and post-market clinical trial data, published or unpublished scientific studies, and reports of clinical use (electronic health record (EHR), insurance claims, adverse event databases, and registries) for either the device under consideration or a substantially similar device.

- Companies can engage with the FDA via the pre-submission process to obtain feedback on the types of evidence necessary for a particular device.

- Further details and examples can be found in the FDA Guidance Documents:

- De Novo classification request

- While the majority of products undergoing the De Novo process do present the FDA with clinical data, there are no specific “hard” targets for outcome thresholds.

- Outcomes from novel clinical investigations are not always required for a De Novo request.

- When data is provided to the FDA, whether it is clinical or non-clinical, it must be sufficient to establish safety and efficacy. Benefit-risk determinations in medical device premarket approval and De Novo classifications play a critical factor in determining appropriateness.

- Companies are encouraged to engage with the FDA via the pre-submission process in order to obtain feedback on the types of evidence necessary for a particular device.

- Premarket approval application (PMA)

- The majority of devices that proceed through the PMA process will require clinical data for approval.

- Companies are encouraged to engage with the FDA via the pre-submission process to obtain feedback on the types of evidence necessary for a particular device.

- The requirements for using data generated outside of the US (OUS) in support of submitting a PMA are notably stringent. According to 21 CFR 814.15, clinical data from OUS sources can be considered in support of a PMA if the following conditions are met: (1) the OUS clinical data are relevant and applicable to the US population and medical practice; (2) the studies were conducted by clinical investigators of recognized competence; and (3) the data are deemed valid without the need for an on-site inspection by the FDA or, if the FDA considers such an inspection to be necessary, the FDA can validate the data through an on-site inspection or other appropriate means.

Related to the use of data generated outside of the US:

- The FDA’s 510(k), De Novo, and PMA programs allow for the use of OUS data, as long as the study population and protocol conform to key requirements. As discussed previously, the standard for using data generated OUS is rigorous, particularly to verify that the device is safe and effective for the US population. Further insights are provided in 21 CFR 812.28.

- The FDA makes a general statement regarding the acceptance of foreign data in its guidance, Acceptance of Clinical Data to Support Medical Applications and Submissions: Frequently Asked Questions: “FDA does not intend to regulate clinical investigations conducted OUS. We expect that foreign clinical investigations will be conducted in accordance with local laws and regulations. The requirements outlined in the rule allow the flexibility needed to accommodate those laws and regulations. The application of a GCP [good clinical practice] standard would be in addition to the local laws and regulations to the extent that the local laws and regulations do not incorporate such a standard. If needed, the rule allows sponsors and applicants to explain why GCP was not followed and to describe the steps taken to ensure that the data and results are credible and accurate and that the rights, safety, and well-being of human subjects have been adequately protected.”

A more complete list of resources may be found in DiMe’s Library of Digital Health Regulations and on the FDA’s Digital Health Center of Excellence website.

Engaging with national regulators

Visit DiMe’s Regulations Resources and Digital Health Regulatory Pathways pages to learn more about DHT product classifications, regulatory authorization steps, and FDA engagement opportunities in the United States.

The federal regulatory agency in the United States is the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA is responsible for “assuring the safety, efficacy, and security” of human and veterinary drugs, medical devices, biological products, and products that emit radiation, as well as cosmetics and the US food supply.

The FDA offers extensive guidance on regulatory requirements and product submission processes on its website. These resources include guidance documents addressing regulatory pathways and common questions.

Review timelines vary according to the program through which a product is submitted. Examples of review timelines include:

510(k) Program: After a company submits appropriate documentation to the FDA related to the 510(k) pathway, the FDA will issue an acknowledgment letter indicating the official date of receipt of the submission and the assigned 510(k) number.

- Within 15 calendar days, the FDA will issue an Acceptance Review result indicating whether the submission has been accepted for Substantive Review. During the Substantive Review, the FDA will contact the submitter within 60 days of receipt of the application to initiate an Interactive Review and/or request additional information.

- If additional information is requested, the submitter has 180 calendar days to provide it; failure to provide all requested additional information within that time will result in the deletion of the 510(k) submission.

- The FDA’s goal is to render a decision on 510(k) applications within 90 “FDA Days” of application receipt. If additional information is requested at either review stage, the company has 180 days to provide it; no additional time will be granted.

De Novo Classification Request: Upon receipt of a request, the FDA will issue an Acceptance Review notification within 15 calendar days. If accepted for Substantive Review, the FDA’s goal is to render a decision within 150 FDA days. If additional information is requested at either review stage, the company has 180 days to provide it; no additional time will be granted.

PMA: The FDA will complete an acceptance and filing review within 45 days of receiving a PMA request. If cleared for in-depth review, the FDA’s goal is to render a decision within 180 days of completion of the filing review.

Breakthrough Devices Program: The FDA intends to request any additional necessary information within 30 days of receiving a request and to render a decision within 60 calendar days of receiving a request.

General questions can be submitted to the FDA by email. The FDA aims to respond, or acknowledge receipt and provide a timeline for response, within 5 days of receipt.

Yes, the FDA encourages pre-submission discussion. Companies may contact the FDA through the Q-Submission Program, which is a pathway for receiving formal feedback from the FDA prior to product submission, either written or in a meeting. Please refer to the guidance document outlining the Q-Submission process.

The majority of applications can be submitted online through the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) portal. As of October 1, 2023, all 510(k) submissions must be made through using the FDA’s electronic Submission Template and Resource (eSTAR). At this time, De Novo requests may be made electronically through eSTAR or by mail through eCopy (instructions), while PMA submissions must be made through eCopy. Q-submission and Breakthrough Device Designation requests are also made through the CDRH portal.

The FDA’s main support structure for regulatory applications is through the Q-submission process, outlined above. The agency will engage with companies during the submission process as outlined in the guidance documents for each pathway.

Glossary of terms

Visit DiMe’s US RegPath Glossary for additional terms.

FDA Day

The number of calendar days between the date a 510(k) submission is received and the date of an Medical Device User Fee Amendment (MDUFA) [Substantially Equivalent/Not Substantially Equivalent] Decision, excluding the days the submission was on hold for an Additional Information (AI) request.

Source: FDA

Least burdensome

The minimum amount of information necessary to adequately address a relevant regulatory question or issue through the most efficient manner at the right time.

Source: FDA

Medical Device User Fee Amendment (MDUFA)

The MDUFA establishes fees that companies must pay in order to have their products evaluated by the FDA. An “MDUFA Decision” refers to the designation of Substantially Equivalent or Not Substantially Equivalent rendered through the 510(k) Program.

Source: FDA

Not Substantially Equivalent (NSE)

A device which fails to meet the criteria for substantial equivalence (see below) to the chosen predicate device. Any device receiving an NSE determination may not be legally marketed in the US until the device is determined to be SE or the device undergoes the PMA or De Novo process.

Source: FDA

PMA amendment

All additional submissions to a PMA or PMA supplement before approval of the PMA or PMA supplement, or all additional correspondence after PMA or PMA supplement approval.

Source: FDA

PMA supplement

The submission required for a change affecting the safety or effectiveness of the device for which the applicant has an approved PMA.

Source: FDA

Pre-submission

A formal written request for feedback from FDA to help guide product development and/or application preparation.

Source: FDA

Q-Submission process

The overall program through which interested parties may request feedback from the FDA in writing or during a meeting regarding potential or planned medical device submissions (relevant pathways: Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) applications, PMA applications, De Novo requests, 510(k) submissions, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) Waivers, Duals, Accessory Classifications Requests, Investigational New Drug (IND) applications, and Biologics License Applications (BLAs)).

Source: FDA

Substantially Equivalent (SE)

A device which is found to be at least as safe and effective as a predicate device.

A device is substantially equivalent if, in comparison to a predicate, it:

- Has the same intended use as the predicate; and

- Has the same technological characteristics as the predicate; or

- Has the same intended use as the predicate; and

- Has different technological characteristics and does not raise different questions of safety and effectiveness; and

- The information submitted to the FDA demonstrates that the device is as safe and effective as the legally marketed device.

Source: FDA

Acknowledgements

DiMe thanks the following organizations and individuals for reviewing components of the United States National Companion Guide, Flowchart, and Snapshot: