What it Takes to Lead in the New Field of Digital Medicine: Being Terrified, Apparently…

I recently froze for a solid five minutes over my computer, hesitating over submitting a comment on a public docket.

There’s lots here. Let’s try and unpack it.

First, what is a public docket and why was I commenting on it?

When a Federal Agency issues regulations — also known as ‘rules’ — they solicit public input to the process. Whether an Agency is responding to a new law or simply seeking to clarify a position or process, they are legally bound to seek public input. This can happen in two phases:

- The Agency may open a public docket to seek early input.

- Any new rule or changes to an existing rule must be posted in draft form for public comment.

Federal agencies are required to consider all public comments when preparing final rules, so the public comment is a powerful opportunity to affect regulatory procedure.

(Full disclosure: until a few years ago I had no idea about rule-making. If you want to learn more, I highly recommend this excellent piece by Mina Hsiang.)

Second, why was this so intimidating?

For the few folks reading this who may know me, “easily intimidated” probably isn’t the first descriptor that springs to mind. However, I was genuinely nervous about engaging in the rule-making process, and I hope it’s helpful if I publicly own that.

My fear stemmed from mis-stepping on behalf of DiMe. I wasn’t commenting as an individual — I was offering up an opinion on behalf of a fledgling organization that will grow to be incredibly powerful, but is currently at a fragile stage of development. The comments we submitted were the result of several months of intense work by an extraordinary and diverse group of experts in the field, yet I worried about being publicly ‘wrong’.

Queue some navel-gazing on what it means to be right and wrong when trying to advance the development of a new field….

There is no room for ego

At DiMe, we are committed to advancing the field of digital medicine to optimize human health. In a few short months we have established a thriving community of hundreds of experts from dozens of countries around the world, all committed to the same goal. We will work hard, we will put patients first, we will be thoughtful, we will be innovative, and sometimes we will be ‘wrong’.

Every day I talk to experts from clinical care, biomedical research, and every flavor of technology under the sun. At least half of them tell me, “I’m not an expert on digital medicine”. My stock response is, “of course you are… because we all are, and no-one is.” Digital medicine is a brand new field and we are only as good as the expertise we bring from our parent disciplines, our willingness to listen to new colleagues, and our commitment to making patients’ lives better.

So what does it mean to ‘win’ in this situation? It doesn’t necessarily mean being right.

While we should be making every effort to move the field forward in everything we do, we have to recognize that is not — and will never be — a linear path. Success should be measured by engagement, thoughtful conversation, and forward progress. In some cases, the best we can do is throw down our best effort and hope that someone picks it up and moves the needle a little further. Could that mean that positions we take are challenged, or even that we’re proven ‘wrong’?

Absolutely.

It’s perfectly OK to make the occasionally mis-step as we push for progress, rather than idly standby and fail to realize the promise of digital tools in advancing health, biomedical research, and healthcare.

What was the public docket that DiMe commented on?

The 21st Century Cures Act requires that FDA collaborate with biomedical research consortia and other interested parties to “establish a taxonomy for the classification of biomarkers (and related scientific concepts) for use in drug development.” FDA is meeting this legislative requirement through updates to the BEST Glossary and the public docket was established to solicit feedback on:

- The utility of the BEST glossary;

- Specific proposed edits, including additions and removal of terms, with a rationale supporting these proposed edits;

- The best approach for developing future iterations of the glossary; and

- Questions pertaining to the BEST glossary that you would like FDA to address in future communications.

This was docket was exciting for a number of reasons.

First, we share FDA’s belief that a common language will help to accelerate development and refinement of medical products, which will lead to improvements in health outcomes. At DiMe, we sit at the intersection of the global healthcare and technology communities and witness first hand the difficulties in communicating across disciplines in the absence of a common lexicon and evidentiary framework.

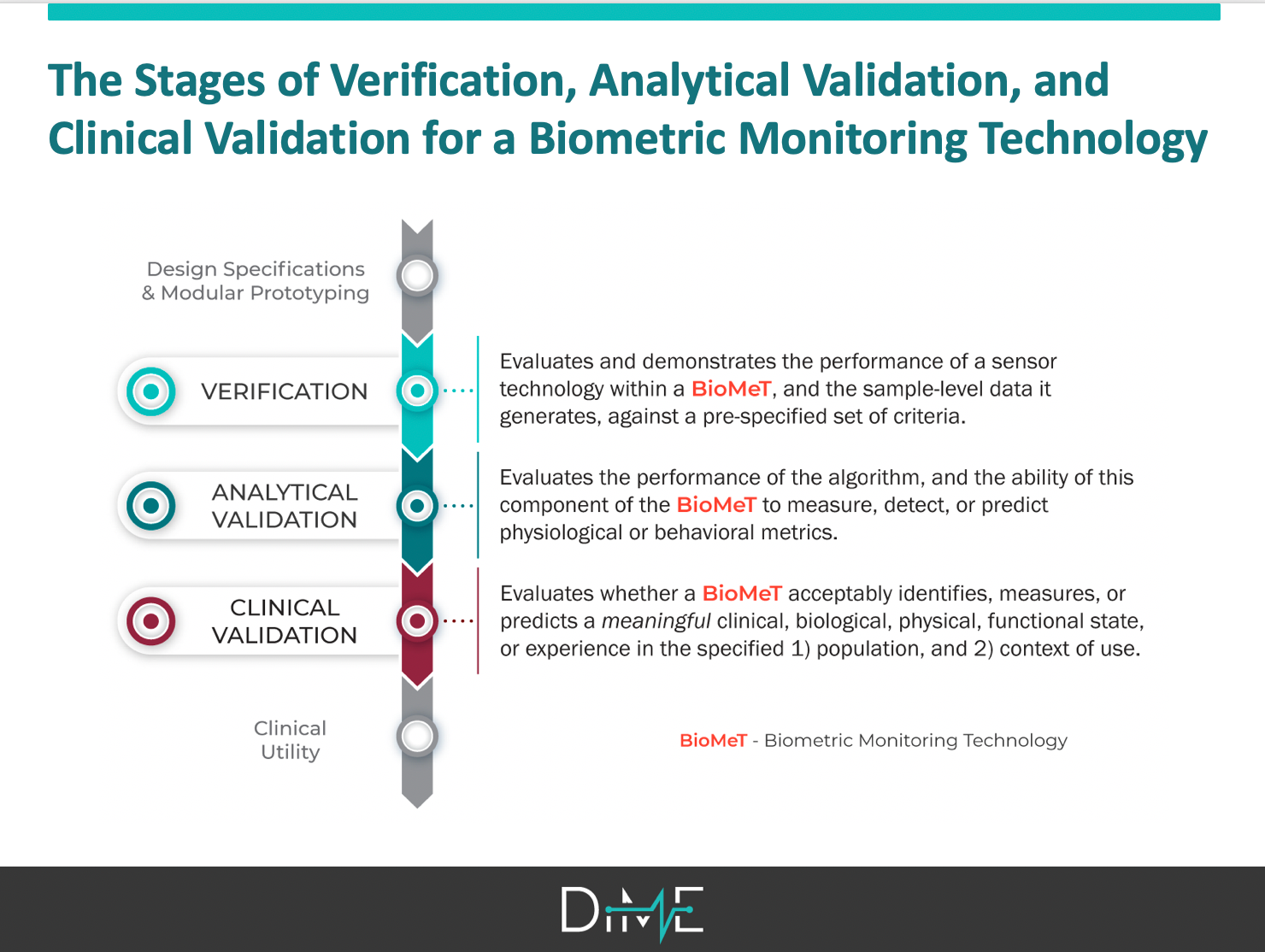

Interdisciplinary discussions of the ‘validation’ of digital tools provide a compelling justification for a common language and evidentiary framework for our new field. Anyone who has ever listened to engineers, data scientists, clinical experts, and even different groups within FDA talk at cross purposes about what it means for a digital tool to be ‘validated’ will understand exactly why this is important.

Second, one of our first priorities after launching DiMe just a few months ago was to clarify the language and evidentiary framework for evaluating sensor-generated measures. After an aggressive sprint by an interdisciplinary group of 16 experts, we submitted a manuscript on this topic just a few days before the docket closed. We had spent months working on the right words and processes for describing biometric monitoring technologies (BioMeTs), drawing on existing terminology from the BEST Glossary that was the subject of the public docket, other disciplines including engineering and genomics, and previous efforts by our CTTI colleagues.

We were prepared to propose thoughtful, specific suggestions for additions to BEST — including the adoption of a three-component framework (V3) for the foundational evaluation of BioMeTs (more on that when our manuscript is published!) — that will support the role of digital tools in speeding medical product development. We were also well positioned to strongly recommendation that, in this new era of digital, future iterations of the glossary must be developed with engineering and data science experts at the table.

Finally, commenting on the docket gave us the opportunity to draw on extensive work we did prior to the launch of DiMe when another interdisciplinary team wrote our Primer on Measurement in Digital Measurement. We had grappled with many of the BEST terms and reflected on how existing definitions of clinical outcome assessments (COAs) and biomarkers could be extrapolated to the digital world. Again, DiMe’s commitment to advancing digital medicine by addressing the challenges that arise when a new, interdisciplinary field emerges, positioned us to have strong, evidence-based comments to offer FDA in our comments.

This included the strong recommendation that the Glossary not be updated to include an 8th biomarker or 5th type of COA to accommodate digital measures. Digital is a methodology for measurement and not a measurement type. As such, the existing framework of seven biomarkers and four COAs should remain intact, recognizing that these now may be assessed using digital tools.

Curious about the comment we posted? They are now live. Ours is available here.

Were we successful?

Yes. We participated.

Our goal at DiMe is to advance digital medicine to optimize health. We cannot do this from the sidelines. We must and will take every opportunity to generate evidence, support communication and education, and foster the community of experts driving the field.

It is also important to note that the comments we offered were the result of hard conversations. In developing both the primer and the V3 manuscript, there were disagreements. Everyone involved had to check their egos and fully engage to listen and learn from the perspective of all experts at the table. To me, this process — this hard, hard process — is the blueprint for building the field. It is not for the faint of heart.

Are we doing enough?

Not yet.

There were only six comments on this docket, yet I believe that the lack of a common language and clear evidentiary framework for the digital medicine is one of the greatest challenges inhibiting the growth of this new field.

We must do more to engage experts from every discipline in this process, including participating in the rule-making process through public comments.

Going forward, we will:

- Share notices of public comment periods that we think may be of interest to our membership.

- Create forums to support anyone commenting for the first time.

Get involved

In that spirit, here are two draft guidances that may be of interest to the digital medicine community that are currently open for public comment:

- Patient Engagement in the Design and Conduct of Medical Device Clinical Investigations, with comment period closing Nov. 25. This draft guidance focuses on the applications, perceived barriers, and common challenges of patient engagement in the design and conduct of medical device clinical investigations.

- Clinical Decision Support Software, with comment period closing Dec. 24. This updated draft guidance includes changes made in response to public comments received on the 2017 draft guidance on this topic (originally titled Clinical and Patient Decision Support Software).

If either of these documents and pertinent to your work, read the drafts… and comment! It might feel intimidating — it was for me — but you cannot be wrong. And if you have questions, or are seeking some colleagues to discuss your ideas with, join us, hop on Slack, and start a conversation.